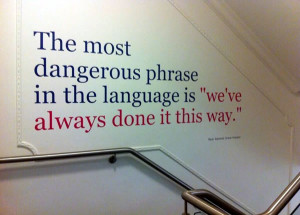

I recently came across a quote from Rear Admiral Grace Hopper that reminded me of our in-class discussion about grammar. She says, “The most dangerous phrase in the language is ‘we’ve always done it this way.'” It’s interesting to think about how often, one of the main arguments people have about sticking to a certain way of doing something is because it is “time-tested,” or worse, based on some nostalgic sense of tradition. I believe the importance of constantly examining what we do and why we do it cannot be understated; as we evolve culturally, the “old ways” of doing various things begin to make less and less sense in light of new technologies, ideas, or understandings.

I recently came across a quote from Rear Admiral Grace Hopper that reminded me of our in-class discussion about grammar. She says, “The most dangerous phrase in the language is ‘we’ve always done it this way.'” It’s interesting to think about how often, one of the main arguments people have about sticking to a certain way of doing something is because it is “time-tested,” or worse, based on some nostalgic sense of tradition. I believe the importance of constantly examining what we do and why we do it cannot be understated; as we evolve culturally, the “old ways” of doing various things begin to make less and less sense in light of new technologies, ideas, or understandings.

As an English Education major, I feel guilty for sometimes wondering about our practices, when perhaps the more loyal act would be accepting them wholly. For instance, in English courses we use MLA format, while in Education courses we use APA. There are no major differences between the two: they both require double-spacing with a legible font, similar margin sizes, bibliographies, in-text citations, and so on. Of course I understand the use of being able to quote from another source in order to avoid plagiarism and to give credit where credit is due, but I sometimes wonder about the necessity of the extremely rigid rules of both MLA and APA, especially for middle and high school students who are unlikely to be publishing their work. Does it matter that their works cited page is indented and spaced properly? That their in-text citation includes all authors’ names on the first occurrence, but then the first author followed by “et al.” for every other instance? Do we continue practices like these merely because we have always done them this way, or because they make the most sense and are 100% necessary?

With that being said, there are some aspects of Standard English that I find to be completely unlike this comparison of traditional practices in that I would not change them even if I had the power to do so. In his essay “The Decline of Grammar,” Geoffrey Nunberg notes that for centuries, people have worried about language because it seems to be constantly diminishing. He states that certain battles grammarians used to fight are no longer even an issue in contemporary times because the mistakes have become so commonplace, they are now accepted as being proper. For example, it used to bother some that “contact” and “process” were becoming verbs. Yet now, we are constantly changing nouns into verbs – “texting,” “trending,” and even “parenting” are phrases used by people of all classes and races. Nunberg’s argument, then, is that maybe language isn’t “diminishing” as much as it is “shifting,” and that our efforts would be better spent figuring out which aspects of the shift are worth worrying about, and I tend to agree. To quote from his essay directly, “Faced with a particular change, then, we need rules of thumb. I submit that the two questions we ought to ask are: Does it involve any real loss? and Is there anything we can do about it? [emphasis mine]” Often, the answers to these questions are “no,” and “maybe,” but I am more inclined to worry about when they are “yes,” and “probably not.” There are a few cases in which I believe the grammar rules we practice today make perfect sense, and if they aren’t broken, why fix them? Even if it seems we have always enforced these rules, and some choose to fight against this (as is logical and important to do), at the end of the day, I believe we should keep the most basic of these rules alive because they are vitally important.

Here are a few examples of times I believe misusing grammar indeed causes us to “lose something,” the argument about “correct” (also arbitrary) grammar being adopted and passed down from upper to lower classes aside:

Incorrect Quotation Marks. Nunberg mentions a rise in the incorrect usage of quotation marks, which I agree with, and think needs to be dealt with as seriously as the recent abuse of the letter “i” (iPhone, iCloud, etc.) – just kidding about that part. I’m serious about the quotation marks though, because I think it’s getting out of hand. See 40 Ordinary Signs that Became Suspicious When People Misused Quotations for more examples like these: If you are “pregnant” please inform the technician, day old “bread,” professional “massage.”

Incorrect Quotation Marks. Nunberg mentions a rise in the incorrect usage of quotation marks, which I agree with, and think needs to be dealt with as seriously as the recent abuse of the letter “i” (iPhone, iCloud, etc.) – just kidding about that part. I’m serious about the quotation marks though, because I think it’s getting out of hand. See 40 Ordinary Signs that Became Suspicious When People Misused Quotations for more examples like these: If you are “pregnant” please inform the technician, day old “bread,” professional “massage.”

Mistakes in punctuation or other grammar that actually change the intended meaning of a sentence, like in these unfortunate examples:

* “Let’s eat, Grand ma,” versus “Let’s eat Grandma”

ma,” versus “Let’s eat Grandma”

* “Try our sausages; none like them,” versus “Try our sausages. None like them.”

* “Slow, Children Crossing,” versus “Slow Children Crossing”

* “Elephants – please stay in your car,” versus “Elephants please stay in your car.”

* “Most of the time, travelers worry about their luggage,” versus “Most of the time travelers worry about their luggage.”

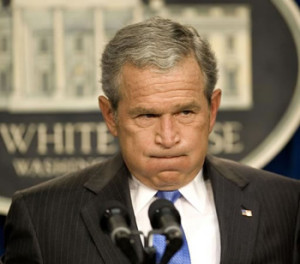

Incorrect subject/verb agreement and other usually-simple-enough-to-follow rules. Perhaps it’s true that grammar rules which make up “Standard American English” are oppressive, and that we should be fighting to change the way we view populations who use variation s of English instead. However – and especially if someone is in a position that lends itself to criticism – judging others for their improper use of English is a pretty natural response. Consider this site, called Grammar Lessons from President George W. Bush, highlighting some of his most embarrassing face-palm moments. Some of my favorites include, “You teach a child to read, and he or her will be able to pass a literacy test” and “It’s a time of sorrow and sadness when we lose a loss of life.” Sadly, my all-time favorite didn’t make the list: “Rarely is the question asked: Is our children learning?” Sorry Former President Bush, I couldn’t help myself.

s of English instead. However – and especially if someone is in a position that lends itself to criticism – judging others for their improper use of English is a pretty natural response. Consider this site, called Grammar Lessons from President George W. Bush, highlighting some of his most embarrassing face-palm moments. Some of my favorites include, “You teach a child to read, and he or her will be able to pass a literacy test” and “It’s a time of sorrow and sadness when we lose a loss of life.” Sadly, my all-time favorite didn’t make the list: “Rarely is the question asked: Is our children learning?” Sorry Former President Bush, I couldn’t help myself.

Of course, these are all light-hearted examples of when grammar has taken a hit, but at the same time, it is easy to imagine when misusing grammar or using language opaquely causes real harm. Some of these instances are outlined in George Orwell’s essay “Politics and the English Language,” and Professor Paku shared an anecdote about a situation with clinical patients that hit home for her. So while it’s useful to wonder about whether an established practice should remain as it is because “we’ve always done it this way,” and even some aspects of Standard English and academic practices don’t always sit right with me, I do believe we should keep in place the most obvious grammar rules such as punctuation use, singular/plural agreement, and subject/verb agreement. We are obviously struggling enough when grammar rules are spelled out for us – the last thing we need is for them to become even muddier, making people look even more foolish or causing even more harm. We can write off other established practices as “stuffy” or in need of revision because tradition doesn’t always trump usefulness or common sense, but correct grammar isn’t one of them.